November 20, 2023

The Path Ahead for Bikesharing

Depending on where you look, you might think shared micromobility is either on its deathbed or poised to continue exponential growth.

This article was authored by Colin Hughes and Isaac Sonnenfeldt of Rebel.

From the United States to Mexico, France to China, to Egypt, ridership and fleet sizes are generally at all-time highs. Yet, industry headlines are filled with dire news of devaluation, consolidations, and signs of contraction. These mixed signals indicate threats to the future of shared micromobility unless cities and private operators are willing to work together to chart a new path forward.

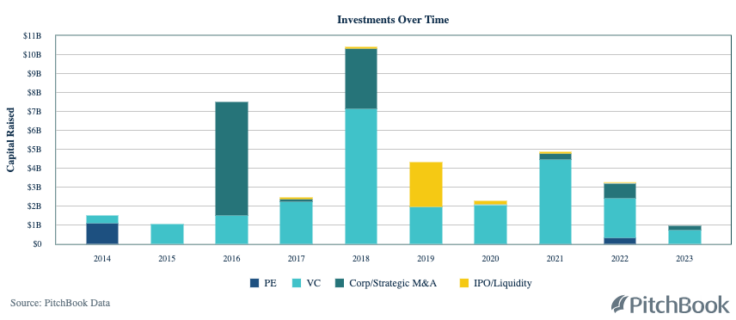

Bikeshare started appearing around 2005, as city governments contracted bikeshare equipment and operations with public funds (or advertising assets), making docked bikeshare a visible part of the urban streetscape. In 2016, growth was accelerated with the introduction of electric-assist, dockless bikes, and scooters financed by venture capital and governed by new kinds of permit programs.

Massive investment and fierce competition between operators fueled exponential increases in ridership and incentivized operators and cities to create micromobility programs that relied on speculative funding mechanisms. As venture capital dried up, so did many cities’ unsubsidized permit programs. Operators could no longer bear the terms that they once readily accepted in pursuit of growth and market share, and the dominant economics of shared micromobility have since come under scrutiny.

While the years of bountiful capital are over, the technologies continue to develop, consumer demand continues to grow, and the operational know-how and proof of public benefit remain evident. The previous era was akin to a large, disorganized, privately funded grant program to experiment with new technologies and demonstrate micromobility’s value at scale. The lessons we have learned from this are now immensely valuable.

The question still stands: how can cities and the micromobility industry incorporate these lessons and work together to offer bikeshare that is socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable?

There is still untapped potential for bikeshare, provided cities and operators can (re)adopt more collaborative, mutually invested, long-term partnerships. We see five main areas where cities can enable better bikeshare: public funding, deeper partnerships, cost-cutting and red tape, electrification, and integration with transit.

1) Public Funding

Bikeshare systems can be affordable, unsubsidized, and equitably distributed across cities, but not all three simultaneously.

Many cities still believe they do not need to subsidize their bikeshare programs, pointing to other systems that are not equitably distributed across neighborhoods, are expensive, are supported by sponsorships, or are relics of the venture capital era. Public transit and private vehicles receive significant direct and indirect subsidies in cities worldwide. It seems backward that shared micromobility—arguably the most publicly beneficial transport mode, considering its impacts on mobility and access, health, environment, and congestion—would be singled out as a mode that should exist unsubsidized.

Where subsidies do exist, bikeshare seems to be thriving—EcoBici in Mexico City, which was recently government-owned and is now privately operated, and Vélib in Paris, which receives 60-70% in subsidies each year, are two of the world’s most successful bikeshare systems, not despite their need for subsidy but because of it. Their equipment is high-quality, the fares are low, and the networks are large and equitable. As a result, these systems have high ridership, reaping considerable returns in mobility and access, public health, environment, and quality of life.

To have equitable, affordable, and successful bikeshare systems, governments will generally need to provide one-time funding for the capital expenditure to purchase equipment and, in most cases, support operating expenditures. They should also be willing to pay more for “add-ons” like equity programs to prevent these critical services from cutting into operator’s margins and disincentivizing them from expanding ridership to all communities. Compared to government investments into highway infrastructure—which amounts to nearly half a trillion dollars annually in the U.S. alone—funding for bikeshare would be relatively minor.

Cities that previously designed policies to extract value from venture capital-funded shared micromobility firms through permit fees, and penalties must now understand that this strategy will no longer serve them. Instead, they should see investments (financially and politically) into bikeshare as an opportunity to deliver high social and environmental returns. A prime example is Denver’s 2021 agreement with Lyft and Lime, where the city sacrificed permit fees but received over 5,000 free memberships for low-income residents and millions of dollars in infrastructure investment from the two companies.

2) Electrifying Bikes and Stations

Riders overwhelmingly prefer electric-assist bikes, even when priced higher than traditional ones, and early studies point to signs that e-bikes might reduce bikeshare’s gender gap. E-bikes increase ridership but are more costly for operators to maintain and keep charged.

One critical opportunity for cities to increase the availability of e-bikes, while dramatically lowering operating costs, is through the electrification of bikeshare stations.

Converting just a fraction of a system’s most popular stations can ensure that most bikes are charged automatically, avoiding the expensive process of manually swapping out dead batteries. Cities should work with local utilities and streetscape authorities to make station electrification more efficient and cheaper. Though we have not yet seen it in practice, cities should negotiate preferential electricity rates for bikeshare use, just as they do for other public uses or entities.

3) Making Bikeshare a Genuine Part of the Transit System

Bikeshare provides a critical public transport service and facilitates millions of multimodal transit trips daily. Yet, only some cities have integrated bikeshare with their legacy transit. We see transit agencies and bikeshare systems benefiting from closer partnerships and shared governance, manifested in the following ways:

- Physical Integration: Bikeshare stations should be featured prominently at the entry/exit of every transit station for easy multi-modal transfers and speedy egress on bikeshare.

- Digital Integration: Real-time bikeshare availability and station-to-station routing can be featured in digital trip planners alongside/as an extension of legacy transit options.

- Fare Integration: Highly price-sensitive commuters are responsive to discounted fare “transfers” between bikeshare and transit, helping encourage mode shift. Transit agencies have much to gain by becoming more meaningfully involved in bikeshare governance and offering discounts for multimodal trips and bikeshare-inclusive transit passes and fare caps.

4) Deeper, More Committed Partnerships

In a recent market sounding that Rebel conducted for the California Integrated Travel Project, the team heard a resounding call from public and private micromobility players for closer collaboration. Private operators need to understand and deliver on urban goals related to equity and mobility, while public sector managers must help to ensure that private sector partners maintain profitability. During the early experimental years, it made sense to create “pay-to-play,” low-stakes, short-term pilots with multiple operators to learn what form factors, operators, and policies work best. Today, stability and close collaboration are also needed.

To achieve this, partnerships and the contracts that govern them should incorporate the following considerations:

- Contract Type: The best, most equitable bikeshare services stem from committed public procurement contracts that offer operators financial support and structured city partnerships.

- Term Length: Optimal term commitments would be 3-5 years with renewal options. Contract terms under three years make investments risky for operators and jeopardize continuity; terms over five years carry the risks of technological obsolescence and outdated or unresponsive service agreements.

- Number of Operators: Gone are the days when more than five operators would compete for permits. While competition has merits, it is better placed in procurement than on the streets. Too many operators create redundancies in operations and fragment users’ experience. Thus, 1-2 operators should be the maximum per city.

5) Setting Operators Up for Success by Cutting Costs and Red Tape

Amid industry consolidation and contraction, cities are now competing to attract operators instead of the other way around. There are many “small” things a city can do to show its commitment to set operators up for success, making entry more attractive:

- Informed and Streamlined Station Siting: Existing trip patterns and user demand should be assessed to help determine optimal locations for stations so that they are situated at convenient intervals. Operators should have a role in choosing station sites and be allowed more efficiency in permitting and installation processes. Learn more about station siting in ITDP’s Bikeshare Planning Guide.

- Reasonable Insurance and Indemnity Requirements: Cities’ legal and risk mitigation teams are often unaccustomed to bikeshare, forcing conservative and costly requirements on operators. As a result, we have seen cities that require shared bikes to carry more insurance than even a rental car. Additionally, some require bikeshare operators to carry the legal risk for damages from the city’s faulty infrastructure.

While the micromobility industry has been traversing hilly terrain recently, bikeshare’s popularity and value proposition to cities is stronger than ever. Cities are poised to leverage the precious lessons from policy experimentation and technological innovation over the past few years. With strategic realignment and deeper partnerships between city governments and transit agencies, private sector equipment producers, and system operators, bikeshare will continue its ascent, making our cities more sustainable and accessible to diverse communities. Together, we can learn from the past to make bikeshare and micromobility more successful and adaptable to the world of tomorrow.

Rebel is Netherlands-based consulting, strategy, and financial services firm working on various issues that affect the future, from sustainability, transportation, and urban development to healthcare and the social sector.

Rebels work around the globe to develop public-private partnerships and innovative financing arrangements, implementing novel project delivery strategies and procurement processes. Before becoming a Rebel in 2023, Colin spent a decade working with bikeshare systems worldwide as a researcher, planner, operator, and policy advisor for ITDP, JUMP, and Lyft.