April 15, 2021

Insights from Mexico City: The Right to Mobility and Work in Public Space

STREET VENDING IN MEXICO CITY

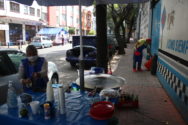

Street vending has been an inherent part of Mexican culture since pre-Hispanic times. In Mexico City, 1.2 million people are part of this informal sector and rely on their ability to work in public space. These vendors make the streets lively and dynamic, and provide people with affordable food and

services that they cannot easily get elsewhere. Whether selling goods from temporary or fixed stalls, and even on bikes, street vendors offer diverse services and products like fresh fruit juice, tacos, and key repair. In Mexico City, they are virtually everywhere: alongside sidewalks, outside metro stations, and in parks. Their omnipresence at convenient locations is part of their value. For many people who spend several hours on public transport, the street vendors outside office buildings provide the only chance to get an affordable and healthy breakfast.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, street vendors ensure low income essential workers can find inexpensive meals. Given that the stalls are outside, with fresh air circulation, and often comply with sanitary measures, they are even less prone to propagating the virus than indoor restaurants. With coronavirus restrictions, many office workers are working from home, drastically cutting their commutes. This has caused the number of regular customers for street vendors to drop. Additionally, local authorities have used sanitary regulations as an impetus to displace vendors from their regular locations since the pandemic began.

STREET VENDING AND MOBILITY

Despite their importance to Mexican cities, some people and decision-makers disapprove of street vendors. To them, street vending does not fit their sense of urban aesthetics and presents a problem to cities. In Mexico City, street vending is not part of the conversation about street design, leaving vendors without an official right to the city. Opposing legislation argues that street vendors constitute a barrier to access and mobility. And because street vendors are often in areas with a high-pedestrian flow, municipal decision-makers perceive them as a physical obstacle. In contrast, for many in Mexico, street vendors offer a convenient way to access goods throughout the day. In some cases, vendors even add eyes on the street, contributing to the perception of safety.

While the right to mobility and work in public space is part of local legislation, mobility is prioritized over work. This means that space for pedestrians and cars is prioritized over space for people to work. Unclear local regulations about working conditions in public spaces also make street vendors highly vulnerable, both in judicial and in material terms. Rather than legislate against them, Mexico needs to improve the planning and design of public spaces to include street vendors. Now, the pandemic places even greater emphasis on the need to safely accommodate street vendors, their clients, and passers-by in public spaces.

STREET DESIGN: THE RIGHT TO MOBILITY AND WORK IN PUBLIC SPACE

With the support of Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), ITDP is proposing a new solution for these rights to coexist in public space:

- Provide safety to all street users. Safety is one of the most important factors in street design, both road safety and social security. Streets must be safe for all: those moving and those working.

- Equitably reallocate public space. Public space is the most important resource for street vendors. While space is limited for all road users, a considerable amount of road space is dedicated to cars. As a result, pedestrians and street vendors are pushed onto compact sidewalks. It is important to increase sidewalks and reduce road space dedicated to cars. While space is limited for all road users, a considerable amount of road space is dedicated to cars. As a result, pedestrians and street vendors are pushed onto compact sidewalks. It is important to increase sidewalks and reduce road space dedicated to cars.

- Include all street users in the design process. In many cases, street design manuals are used to reorganize public space. However, these manuals do not consider how to include street vending in street planning or the final design. To understand the needs of street vendors and pedestrians, both users should be included in the street design process. Cities can do this through various strategies like workshops, participation platforms, and tactical urbanism.

- Consider street vending viability in street redesign and public space reorganization. When considering the reorganization of public space for the street user, street vending viability and flexibility need to be considered. It is important to analyze the pedestrian flow and the street space, so users can coexist without hampering each other.

Street vending has been part of urban life for many years, and this current crisis has merely underlined its vast contributions to street life and the well-being of millions of people in Mexico City. Without recognizing street vendors as part of the natural fabric of the city, legislators do a disservice not only to the many vendors but all the pedestrians; in rethinking urban spaces, street vending must not only be considered, but included in planning. Mexican cities can create space that is not only more equitable, but will ultimately be beneficial to the many patrons of the vendors, as well as all street users; inclusivity will improve the streets for everyone.